Building Zero Zero Island

Scott Schleh remembers watching his father airbrush posterboard and paint acetate to create television's first color cartoon in a studio with a pool.

During the dawn of television, studios across the country started popping up to provide content for the stations that were popping up just as quickly. One in particular, named Soundac, sprung up in the middle of Buffalo. Soundac, founded by musician Bobby Nicholson (replaced by Robert Buchanan a few months later) and artist Jack Schleh, began with fairly generic television shows such as Dollar Derby and Tune-O in 1951. In 1955, Soundac and its employees moved to Miami, Florida.

Scott Schleh, Jack’s son and now 75, remembers the unique move. “The initial building [before it was bought by Soundac] was a great big warehouse … it was a trucking company, and it had a huge parking lot. Right out in front of the building, there were a couple of buried fuel tanks … right in front of their garage. They had to take those [out], since they weren't in use anymore … so it left them with a big giant hole right in front of the building and they just decided they would put a swimming pool in there … they designed this … swimming pool and put a patio around it, and then they built the rest of Soundac surrounding the pool … a ring of offices and rooms.

“You had a pool in the middle, the big warehouse building to the rear, and then a wrap around of smaller rooms and studios that housed their dark room, their artists, each artist had a separate little work area, a little studio, and they added a reception area and a screening room … a big dark room and another room for their Oxberry animation equipment stands in their area … [and] Buchanan had a penthouse on top of the big building … it was in the entire apartment on top of the building, that was his bachelor pad up there, and also he could be the onsite caretaker of the building, it wasn't in a real great area of town, and he was sort of keeping an eye on the place and be there basically all the time. But he lived in downtown Miami there while my dad and most of the other artists and people lived out in the suburbs. … Buchanan had got into scuba diving, and he would sort of practice in the pool … it was neat to have that as part of Soundac.”

With the new studio, Soundac entered the animation world with the children’s quiz show Watch the Birdie. Watch the Birdie had little animations play on screen when a contestant got a question right, animated by Jack Schleh himself using a new limited animation method he had been developing with Soundac’s Oxberry animation stand.

“… [My father] was always artistic,” said Scott, “I don't know [why] he got interested in animation, but he wanted to do animation way back in the early 40s, maybe even late 30s. He was working in the advertising department in a major department store in Buffalo [named Sattler’s] doing advertising art and my mom was a fashion artist in the same magazine and that's where they met. But then everything [got] interrupted by World War II and my dad signed up in 1941, he volunteered and he had figured out he was going to join the Army off of all these choices, he was going to join the Signal Corps because then he figured he could get in with famous directors, they were making basically American military propaganda films of all kinds of nice high tech animation at the time anyway and paid for by the government to do these films about patriotism … and so my dad said, man, I'd love to get in on that so he joined the Signal Corps but by the time he got called in [they] said … ‘we've got enough artists to volunteer in, but you're in the Signal Corps, the Signal Corps is audio and visual, so we're going to make you a radio man’ … and the Signal Corps job was basically a cypher decoder … he worked both in the US Army and also in the British 8th Army in North Africa, so he'd be right there where the generals were camped out at night in his little unit there and they would be getting coded messages … but he never got shot at … he got back with my mom who had been writing letters to him all the time and they got married … then I was born in 1949 and my sister in 1951, both up in Buffalo.”

Along with Watch the Birdie, Soundac was also producing an assortment of commercials (reportedly 4,000 by the end,) all being animated by Jack or his co-artists Fran Noack, Hal Lockwood, and George Ghyssels. But in 1957 Buchanan and Jack had come up with a new show titled Colonel Bleep, a sci-fi animated television show about a martian (specifically called a Futuran) named Bleep and his adventures with his friends Scratch the caveman and Squeak the puppet. Bleep was designed to be cost effective but also to fill a void. Finding animated content to schedule for broadcast was difficult for stations without re-airing the same theatrical short subjects over and over. Colonel Bleep was the first show to be made specifically for television in color, in an age where color television was still brand new.

While Buchanan and Jack wrote the first two episodes (often used as a pilot to pitch to distributors) it was Jack who wrote and animated the later 98 episodes. (Originally, it was intended to only be 52 episodes, however this was extended to 100 after a broadcast executive had sold the show for 100 episodes at 39,000 using only one storyboard.) “He'd have to come up with a new episode every weekend,” said Scott, “which he did. [Every] Monday morning, going there and he'd have the plans for the next week's episode and they would do an episode a week, which was pretty amazing for the small little staff like that … they would whip out one episode a week.” Jack Schleh would often read encyclopedias for ideas on future episodes, which often lead to their unique and sometimes strange situations.

“Colonel Bleep was all done basically with the acetate cells with white tempera paint. … For the other characters like Squeak and Scratch, they made full sheets of photostats photographed in black and white of all the various body parts in scale. So you could cut them out like a paper doll sort of thing and cut and paste and have their arms and legs or whatever, whatever they're doing, you would have all our various body parts. You could move and reposition [them] to walk or or wave their hands or whatever they're doing. So they would just glue those pieces onto the one layer of the acetate. They can keep the body on one layer and have the arms and legs in a couple of different layers and they would just switch them back and forth as they were shooting the animation to make it move.”

“[They had a] stack of several layers of acetate on there, but they flattened out real nice and color came through beautifully. They had these super neat backgrounds that he had painted [with] vivid colors and all that. The camera guy would, after taking each frame, move the background a little bit. They're big long panoramic things, like three feet long by about eight inches tall. And he had a little library of them that got bigger as it went along, but they would pan figures and do their action over that. [Bob Biddlecomb] shot everything. He was like one of the core people of Soundac. … He would just sit there in his little dark room with the Oxberry animation stand. A couple of bright lights shining out on the artwork and he would have a cable release in his hand and a counter on the Arriflex camera. He would pan and zoom according to the script all day long. I just remember seeing him there with a coffee cup and a pack of cigarettes. But that's what he did. He did it for years and years.

“They hired a local announcer personality [Noah Tyler] to do the voice over and tell the story. … [Bleep’s] only way of communication was his bleeping noise that kept the dialogue down, saving a lot of extra steps. … But [Scratch,] the only noise he made was a scratching noise, so they called him scratch and the third one was [Squeak, and] he would squeak when he moved around.”

Along with the steady release of 100 five minute episodes, there was also a short pilot for the show proposed with wrap-arounds using a host and an audience of kids for a sort of kiddie quiz show. While this concept for the show was never picked up to be produced by Soundac itself, it seems that some stations would do their own variations of the same idea.

Colonel Bleep had a sizable success upon release, with merchandise being sold in stores and sponsorships by companies like Red Goose Shoes, Maypo Cereal and 7-Eleven.

As Bleep continued to air on television, Soundac expanded further into other ventures. One project that Jack had no involvement in was Weather Man, a series of short animations for various weather forecasts created by artists Fran Noack and Hal Lockwood. Weather Man was sold to stations across the country to be shown between commercials as a short weather report.

Later on, Jack came up with Info-Maps, a tool for the news. Jack drafted his own maps of various countries around the world and designed stickers to be applied to them to show where certain disasters or events have occurred. Info-Maps were used by news stations across the country for the next decade or so, becoming such a success that Scott remembers them laying around the house to be used as scratch paper.

Soundac would continue to produce industry tools such as station ID’s and Super-Fex (small animations that would be placed on top of television shows.) Later, Soundac was hired to promote the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair on television with animations also directed by Jack.

Starting in 1963, Soundac had a new colossal franchise up their sleeve, titled Mighty Mister Titan. During the Kennedy presidency, Kennedy advocated strongly for the physical fitness of Americans, especially in youth. To cash in and promote this American goal, Mighty Mister Titan was a show of 100 segments meant to help children across the country exercise. Titan even got as fair as being approved by the Consultant to the President on Physical Fitness, officially being endorsed by the White House and having its own “Mighty Mister Titan Physical Fitness Team.”

Unfortunately, when Kennedy was assassinated on November 23rd, 1963, so was Mister Titan. “They thought it was going to be one of their biggest hits, but my dad [Jack], he said [Titan] died with JFK. They did continue to work on it, but they had to redo a lot of stuff … they had to rewrite any references to the president, there were quite a few references that ‘President Kennedy needs nice healthy young boys and girls like you to help run the country in the future,’ and blah, blah, blah, but they had to do a lot of re-editing and they eventually released it, but it was not a big deal at all, I guess they probably broke even on it, but it was not what they were hoping for, but that's the way it goes.” Said Scott.

Out of 100 episodes, only 6 have surfaced online, with a handful of others existing in private collections or rotting away in archives. It’s unknown how many were aired in the first place.

Around this time, Soundac also produced one of the first animated Mountain Dew commercials. However, there’s conflicting accounts on whether it was done before or after Pepsi had made Mountain Dew a national drink. Mountain Dew’s famous slogan “Ya-Hoooo Mountain Dew!” originated from Soundac, though it’s unknown whether or not it was Jack or Buchanan’s idea.

When Jamaica gained independence in 1962, Soundac was also given the chance to do a variety of commercials for the Caribbean area all throughout the mid 60s. Scott said that “I got to go to Puerto Rico a couple times, I went to Mexico, … Puerto Rico, I spent a little bit of time a day or something in the Dominican Republic and Jamaica and Haiti and every place along the way, except Cuba, which was off limits at the time, but it was neat to experience because my dad would have the family tag along as much as possible on his business trips, just for general fun, which we had a lot of in the islands and stuff.”

In 1969, Jamaica passed the Decimal Currency Act, changing from shillings to dollars. Soundac was given the responsibility to produce the animation for a PSA for the country in explaining its citizens the conversion and introducing the new currency. This film was titled “Decimal Currency ‘69,” whose animation was done by Jack Schleh as well.

By the 1970s, Soundac was ramping down on production. While it isn’t known when the studio officially shut down, Jack started his own design group around this time and continued to work as a designer well into the 80s.

Meanwhile, in 1986, animation historian Jerry Beck moved to L.A. and would have “cartoon parties” with his friend at the time John Kricfalusi (the cartoonist who later created Ren & Stimpy.) Beck would bring stacks of 16mm prints of various films from his collection and Kricfalusi would do the same. However one day, Kricfalusi had asked Beck to instead “bring over the worst". Beck recalled, “So I brought things I considered bad and I haven't watched in years at that point in 86. And one of those things was Colonel Bleep. The only reason I remembered it was because it had very limited animation. I saw Colonel Bleep on TV when I was a kid. I grew up watching it. That's why I had it in my collection. I mean, it was something that was nostalgic to me. … There was all the guys who'd become the future superstars of Spümcø … All the crummy stuff [like] Clutch Cargo got laughs. But Colonel Bleep, everybody, including me, we all noticed the artwork in this was really good. We all just rediscovered it at that moment. … He [Kricfalusi] was fanatic about Colonel Bleep at that point. I ended up trying to find as many Colonel Bleep cartoons on the collector's market as I could just to satiate his appetite.” Later on, Colonel Bleep’s intro sequence would be referenced directly by Kricfaulusi in the Ren & Stimpy episode Space Madness.

In 1988, Beck would co-found Streamline Pictures who would be the first to release Ghibli films such as Laputa: Castle in the Sky and My Neighbor Totoro. a few years later. However, they wanted to expand to other kinds of releases as well. “We wanted to do more than Japanese animation and we were at some TV convention, a convention of people who have TV shows that they want to sell to local stations. And there were people there who have had the rights, or at least they said they did to a lot of oddball programming, and oddball programming was exactly what we wanted to do. Maybe it would be cheap to get, but it would be something we understood that we thought was had merit, but was overlooked by the major studios … We talked to those people that had Colonel Bleep and they had Space Angel and and Clutch Cargo. We made a deal to put them out and as part of that they gave us their “master material,” which at the time, for all the shows, were 16mm. I keep thinking the Colonel bleep stuff might have been negative … in theory it was the original negatives.

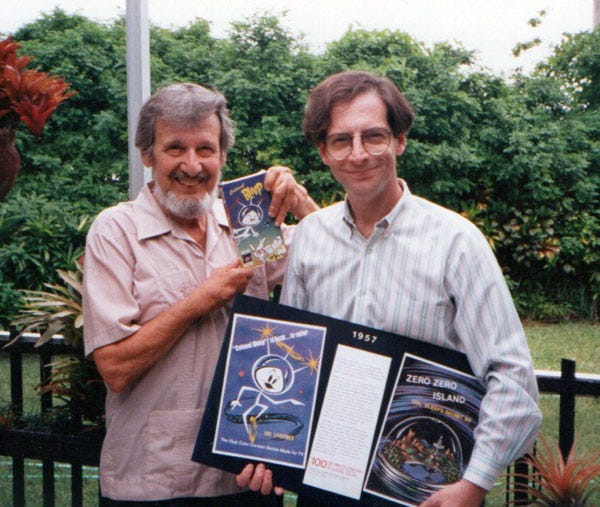

“I don't know how I did this exactly, but I somehow figured out or found my way to Jack Schleh. … He found us and wrote to us and I started a communication with him. Then that year I was going to my family that lives in Miami, Florida in that area. It turned out that Jack Schleh lived like a mile away from my grandma. So I went down and I visited with Jack Schleh. … I cared so much for what he was doing and what he was up to. For us who recognize Colonel bleep and Jack Schleh's artwork in later years, I'm very proud to be someone who represented everybody who in the future would recognize his artwork, because he didn't have anybody at that time. There were no retrospectives or anybody discovering. We were the closest thing to it at that time. He appreciated that. He even drew us new Colonel bleep, little paintings thanking us for putting it out and that kind of thing is really, really cute and he still had it, he could still draw and paint and everything.”

In 1991 Streamline Pictures released two volumes of Colonel Bleep on VHS, the first time Colonel Bleep had ever been released on home video. Originally meant to be released as five half-hour volumes, unfortunately things like Colonel Bleep and Clutch Cargo didn’t sell well compared to Japanese animation, so the later three volumes were dropped. Luckily, apparently Colonel Bleep- or at least the first two episodes- had entered the public domain in 1985 due to not having its registration renewed (a requirement at the time.) The rest of the series, it seemed, had been public domain since release due to never being registered in the first place. Because of this, companies that specialized in public domain releases like Alpha Video, East West Entertainment, and Mill Creek Entertainment, would release various episodes of Captain Bleep over the 2000s. In the end, 35 episodes have been released on Home Video, with another 10 being uploaded online from other sources.

In terms of Soundac’s work, or more specifically Jack Schleh’s work, it seems much of it hasn’t survived. Scott said that “he wasn't a pack rat when it came to Soundac. … he didn't save much, you know, I wish he had. I [have] a can of film that might have been some lost Bleep episodes. I finally opened it up, but having been in Florida heat and humidity for 70 some odd years or whatever it was, the thing was all gelatinous goo inside there.” As tragic as this sounds, this reel may have hope if in the right hands.

Fortunately, it seems, episodes of Colonel Bleep and the rest of Soundac’s catalog surface every now and then. Jerry Beck himself has said to own at least ten episodes of Mighty Mister Titan on 16mm film (one of which he presented himself on the DVD release Worst Cartoons Ever!). While it’s not known if the entire show has survived the decades, it’s almost certain episodes not seen for years will turn up. It’s just a matter of finding them. Much of Soundac’s reputation, like most commercial studios of its time, has been forgotten. Thankfully, however, Colonel Bleep has managed to stay afloat and remain remembered, especially by the son of his own creator.