Creating Dog Eat Dog: The Unrealized Game of Corporate Drama

From Dragons to Dogs, Darlene Lacey talks about a game that never had the chance to be played.

In 1991, Darlene Waddington (now Darlene Lacey,) a developer at Disney Computer Software and previously a designer on Dragon’s Lair and Space Ace, had the idea of a new computer game inspired by her experience working in the typical American office. Though it would have been Disney’s first adult video game, covered in multiple computer and gaming magazines, as well as one of the first games to use a neural network, it unfortunately never game to be. It is, however, fondly remembered by her and her team. When asked to tell the story about Dog Eat Dog, she recounted the memories of creating a game that wasn’t comparable to anything else on the market.

ZC: Let’s start from the beginning, how did you get involved with Buena Vista Software?

DL: In late 1988, The Walt Disney Co. decided to enter the videogame and computer game market. They named their new division Walt Disney Computer Software, known under the brand name “Disney Software.”

In 1989, they hired me as a game producer, one of three recruited to lead the way into this growing lucrative market. My colleagues were David Mullich (The Prisoner, Dark Seed II) and Sam Palahnuk (Star Trek: Strategic Operations Simulator, The Animation Studio, Wolf).

Sam recommended me for the role. We had worked together a few years prior for Sega Enterprises and Gulf+Western to design laserdisc coin op games. Among other things, we were creating a Star Trek laserdisc coin op, Star Trek III: The Phaser Disc Game. However, the bottom dropped out of the laserdisc market before we could finish it.

The Sega team was a small group of experts, and we enjoyed working together. I was one of the few people who had ever designed laserdisc videogames, so that’s what brought me there. I had worked from 1981-1983 at AMS (Advanced Microcomputer Systems), where I was one of the designers of Dragon’s Lair and Space Ace.

When I joined AMS, I was finishing my degree at nearby Cal Poly Pomona in Broadcast Communications. I was an aspiring writer. AMS hired me to write interactive fiction for an experimental home game system (later to be known as Halcyon by RDI Video Systems). I really enjoyed writing interactive fiction and thought it was a medium with much potential.

Skipping forward to 1989, when I went to work for Disney, I produced and designed some low-budget titles and produced some licensed NES titles (which have brought me some fame, most notably DuckTales). These projects were fun enough, but I wanted to do something more creative---something innovative with interactive fiction. So, I began pitching original ideas for story-based adventure games. Dog Eat Dog, or Big Time, as it was originally titled, was one of them.

Management liked my ideas, but they were concerned that they weren’t entirely “family friendly” and not based on Disney’s intellectual property. I proposed that we start a “Buena Vista Software” label, like Disney was already doing with their movies. As things turned out, Disney Software released some titles using that label, but none of my projects ever came out on it. Still, you will see the “Buena Vista Software” label on early versions of the game because that was the plan. Please note: This Buena Vista has no relation to the Buena Vista Games, which started over ten years later.

ZC: Where did the idea of Dog Eat Dog come from? When?

DL: My inspiration for the game came from the temp job I was working before I joined Disney. I made ends meet with temp work while I was working on some novels. Temp work was an eye-opener for me. As a game designer, I had been treated very well; as a temp, I was treated like a lump of meat. Same person, different context. For example, one morning I found my desk and chair gone (I was the receptionist). The phone and computer were just sitting there on the ground. Turned out that HR had taken them overnight to give to a “real” employee they had just hired. They told me to just figure something out.

This company was dysfunctional, all the way down to the asbestos-filled building. The nurses on the floor above us went on strike to have it removed, so it was cleared out of their floor and left on ours. There was a bird’s skeleton in the storage closet behind my desk. Apparently, it had been trapped during construction and remained there for decades. Nobody bothered to remove it. It seemed symbolic of the whole culture there. The HR Director admitted that he hated people. I had to run around the office at lunchtime, hiding behind filing cabinets because a guy in IT kept chasing me in the hopes of a romantic tryst. I have many, many stories.

So, this experience left me thinking about how we spend eight hours, five days a week in these work situations. We like to pretend that this is not our real life---but it is! So, how does one find happiness or success in a situation like this? How does one navigate a toxic environment filled with toxic people? What an adventure that would be! I proposed that we turn this experience into an adventure game. Management loved it. Keep in mind this was before Dilbert became well-known (I didn’t hear of it until a little later), and long before the movie Office Space. This was a novel concept.

ZC: Who was in the team?

DL: Our developer was a young team named Open Mind that had come to the office to pitch another concept. They had no game experience, but they were brilliant and interesting, coming from Cal Tech, Harvard, and Cal State Berkeley. They were/are Mitsu Hadeishi and Doug Cutrell (architects/programmers), and Susan Chow (writer). I wrote a large amount of the scripts as well. Later, as the project grew, we added more people: Tamara Williams (writer), Jimmy Huey (programmer), Pat Thompson (music), and Jack Levy (sound effects).

ZC: Who was the main artist? What do they do now?

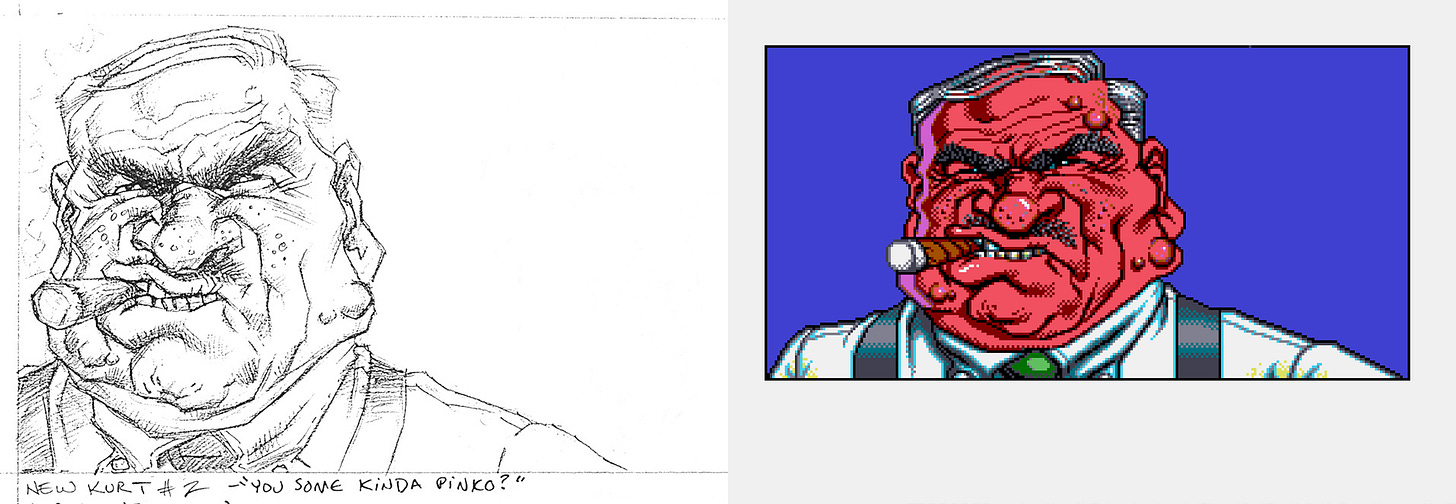

DL: The art was done in-house, which was an exception to the contractor rule at Disney. Jeff Hilbers, Disney’s art director, recruited his former Cinemaware colleague, John Duggan, to come work for Disney and be the game’s principal artist. John had done great work on Cinemaware’s TV Sports and Wide World of Sports Amiga games and made some fine supporting art for other beautiful Cinemaware games such as Wings that Jeff was lead artist on.

John was perfect for Dog Eat Dog. He had a subversive sense of humor and drew underground comics. After Disney, he worked on a number of Sega Genesis and Nintendo DS games. I don’t know what he’s doing now. Jeff Hilbers, who believed passionately in Dog Eat Dog, also contributed a great deal to the Dog Eat Dog art. He later went on to work on several titles for Mass Media Games.

Cinemaware, famous for its richly rendered graphics, were leaders in this trend in which the industry was going. However, for Dog Eat Dog, I wanted something different---a 2D pop culture comic strip look, sort of a cross between MAD Magazine and Roy Lichtenstein. I wanted this for multiple reasons. First, I wanted to highlight the theme that the working world can be a total farce. Also, I thought a thin 2D surface would strengthen the concept that the office world is paper-thin. And, by keeping the graphics simple, I thought players would more deeply focus on the heart of the game, the story. I also wanted this game to be fresh and novel in every way, and by putting a “face” on it that defied industry trends, we would instantly make that statement. Last but not least, this approach was pragmatic; we could create a huge simulation on a tight budget and timeline. We only had 1.5 artists! Oh, how things have changed.

I want to also say: It's gratifying to me to hear that the graphics are what still attract interest in this game. They came out fantastic!

ZC: Was there a specific plot? Or was it more open ended?

DL: The story was open ended with a loose plot creating a narrative thread. We wanted to make sure that players never felt like they were being driven down a predetermined path, which was the flaw of so many text adventure games.

We designed several “winning” endings so that players could “win” on their own terms. You could rise to CEO, leave to start your own business, quit with dignity, find your soul mate, etc. We wanted people to play it again and again, trying different approaches, discovering new outcomes, and learning something about themselves. Of course, there were many, many ways to get fired, and the game might end with the HR Director blowing up the building.

To make all this work, we wrote scenarios, more than enough for one playthrough. They were all open ended. The non-player characters would treat you differently in each one based on your previous actions. Even if you never met an NPC before, they might already have formed an opinion of you because they were friends with someone you interacted with earlier in the game.

To also keep things unpredictable, we had the player navigate the world purely by “intention”…kiss up, argue, hedge, flirt, brag, etc. Traditionally in text adventure games, players chose dialogue from a menu. In ours, the words that came out of the player character’s mouth were a complete surprise. You were not in total control! We wrote banks of dialogue for each intention so that, for example, there were dozens of lines if you “kissed up.” Then, the NPC drew from a bank of responses (such as “put downs.”). We scripted the lines so that they could be used generically or only in a certain context.

We wrote a vast amount of dialogue, but we would need it for the neural network. However, the neural network proved too ambitious. Mitsu and Doug had to eventually switch gears to developing a custom conversational AI language and editing system along with an integrated development environment for that language. It was called ConEd (Conversation Editor). We writers used it to playtest the scenarios and finetune them.

ZC: How adult was this game meant to be? Details Magazine jokes about sleeping with your boss and Sue's writing sample has Joe flirt with Floyd.

DL: Nobody at Disney was doing anything close to it. It was Open Mind's idea to give the player the ability to flirt with an NPC of any gender at any time, which was an idea ahead of its time. It was a bit controversial, but we had the okay from management. And even though you could sleep with the boss (and marry the boss), there was nothing graphic. The game was told almost 100% through our little talking heads and text panels that would fill in the parts of the story that couldn't be shown. The "raciest" thing we had graphically was when the VP of Manufacturing is caught kissing the ancient executive secretary.

But, considering that the game could end with the whole company being blown up by a bomb in a doughnut box (with or without you), you know it was a pretty edgy game! You could also die of food poisoning from eating a tainted Sludge candy bar in the snack machine.

ZC: I read there were development issues, what happened?

DL: It was taking too long to create the neural network game engine. Disney loved the game, but we were nowhere close to completion under the original schedule. Open Mind worked a lot of extra hours for no pay to honor the agreement. We all believed in this game and wanted so much to bring it to the world.

I think we began the project in summer 1991. By spring 1992, we still didn’t have a first playable, and the project was in danger of being cancelled. Disney was going to the Summer CES (Consumer Electronics Show) in Chicago. I begged management to let me demo the game there to prove its potential, promising to have a demo ready. They agreed, and our team worked full speed to build a demo (not using the neural net) just in time.

At CES, we got a flurry of interest from the press, including CNN’s Showbiz Today, which you can see on my YouTube channel. The game was also profiled in Popular Science, PC World, and Details Magazine. We had interest from other major publications to do features once we released the game, which, alas, never happened. But my strategy paid off, and the project continued.

ZC: Does that CES demo exist anywhere in a compiled format?

DL: Regarding the demo, I think it would be relatively easy to run. It was just a DOS program. However, I don't want to just give it out. I will tell Mitsu about you and your friends being willing and able to help with something like this, though, and he can make the call on what happens with anything regarding the code! It would be nice to have a running version of this.

ZC: The game found a new life at Trilobyte, how did that happen?

DL: While all this was going on, other events happened at Disney, causing an overhaul of Disney Software in 1994. All projects in development were cancelled. We were desperate to save the project. Jeff Hilbers used his used his Cinemaware connections to sell it to Trilobyte, founded by former Cinemaware art director, Rob Landeros and Virgin Games’ former VP of Research & Development, Graeme Devine. Jeff Hilbers and I left Disney and joined the Open Mind team. We named our new company Ministry of Thought.

ZC: Why the change to FMV?

DL: When Trilobyte first acquired Dog Eat Dog, they planned on letting us complete it as a nice complement to their portfolio. They were hugely successful with their first release The 7th Guest, but FMV games took a lot of time, technology, and money, and they were still working on the next title The 11th Hour. However, as much as they appreciated Dog Eat Dog, they soon determined that they could not publish a title that didn’t use their “secret sauce,” their advanced FMV.

We knew this decision was disastrous; the game was too huge for FMV. The scripts were not written in a way that one could easily pare them down. After discussing all our options, we decided to make it episodic, and the first release would be a small introductory part of the game. Even then, we had to hack away most of the open-ended elements, and Trilobyte spent $300,000 on the video. They used a green screen so that they could also build 3D environments created by their own artists.

You can imagine our dismay that they weren’t going to use our art. We also felt that using actors took away all the important themes that we wanted to underscore with the 2D approach. We were concerned that this would look like a sitcom instead of subversive underground comics.

ZC: How much of it was finished? Why was it canceled?

DL: The project pretty much died soon after. Trilobyte was faced with taking on a huge video editing task, creating all the 3D environments, debugging, etc. while they were still working on finishing The 11th Hour and starting on another FMV project, Tender Loving Care. Dog Eat Dog was never supposed to consume so much of their resources. So, they let Ministry of Thought go to save money. They planned on finishing it in-house.

However, they never did, and we wound up buying the IP in 1999. We didn’t have a plan for it; we just wanted this creation that we loved and worked on together for eight years to come “home” with us. We have never had an opportunity to finish it or revive it, and that’s okay. We needed to move on to other things.

ZC: I’m a big fan of how the game looks and its premise during the Buena Vista era, would you consider sharing what you have left? Anything between files and sketches … I would also be curious to see what was shot for the FMV version.

DL: Certainly! I have kept a lot of ephemera and content from my career. I have the FMV on DigiBeta. I don’t have a deck, but trust me---there’s not much to see. A lot of raw footage on a green screen. I also have the original sketches for the 2D art along with all the art files. I have my original proposal and other fun things like that. I can share some with you. Ministry of Thought is a thing of the past, but Mitsu still has the code, and he, Susan, and I are still contemplating creating a version of the game using today’s technology. I’ll let you know if and when that ever happens!

ZC: What are your thoughts on Dog Eat Dog, looking back?

DL: I think that if we were to release it today, it would still be groundbreaking. It’s too bad that it didn’t make it, but I learned the hard way that just because something is great, this doesn’t guarantee success. The project was probably doomed from the start because Disney Software only made games that were low budget with tight schedules compared to the industry norm. This game was too big. We needed more time, a bigger budget, and a larger team. Had we had those things, we could have made it.